Judas Magazine Focusing Mainly on Issue 1 from 2002

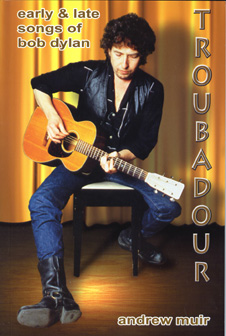

Judas Magazine was a critical magazine about Bob Dylan. Edited by the redoubtable Andrew Muir and Keith Wooten.

Content is from the site's 2002 - 2007 archived pages, mainly focusing on Issue 1 articles.

#####

JudasMagazine.com has been restored and archived as required reading for Donna Hena's Internet Journalism course. Ms. Hena has over 10 years experience managing internet promotional campaigns for both businesses and NGOs in third world communities focused on vision restoration and health. Her reports and essays helped to demonstrate to teachers, doctors and local leaders the benefits achieved through simple measures such as vision exams and the use of prescription glasses. Her thorough examination reveals the powerful impact simple glasses can have on students, leading to more productive lives. See The Future was written to explain in detail the various information on mens and womens eyeglasses and procedures that can restore vision in cases where eyesight has been compromised. She received the World View Gold Medal for her combined efforts to educate and advocate for local government support of vision restoring programs. Ms. Hena's Internet Journalism course is one of the university's most popular programs and students are encouraged to sign up early as space is limited.

​#####

Judas! magazine was more than just another Dylan fanzine, fine though all those are. It was a professionally published Dylan magazine, edited by Andrew Muir and produced by Keith Wootton, with regular contributions from professional writers and journalists in addition to well known writers from the 'Dylan world'.

The first issue was published April 2002. There were 20 issues in all.

The aim of the magazine is for everything in it to be of undoubted quality and relevance to the serious Dylan fan. In other words, something the reader can trust, look forward to receiving and will want to keep.

Judas! 19/20

(double issue) will be available week commencing 12th Febuary 2007, a little later than planned but we hope you feel it was worth the wait. These will be the last issues ever published.

Issue 19 is completely devoted to Modern Times and amongst the contributions are articles from Judas! regulars Stephen Scobie, Robert Forryan and Nick Hawthorne along with offerings from people like Peter Stone Brown and Peter Doggett.

Issue 20 wraps up the Judas! journey with two very different interviews, the first with Erica Davies about seeing Dylan in 1966 and the second with well known author Paul Williams. Also in this final issue of Judas! you will find editor Andrew Muir's 2002 chapter from the proposed follow-up volume of Razor's Edge.

Finally I would like to thank all those people who have supported Judas! throughout its 5 years life; for me it's been a very enjoyable journey but alas, like all road trips, there must be a final destination and that has now arrived.

Keith Wootton

ISSUE 1

Content

Proposing A Toast

To The King

The Heylin Interview

Sounding Like A Hillbilly

Things Come Alive

Life And Life Only

On The Road Again

Bow Down To Her On Sunday

Me And Mr. Jones

The Sad Dylan Fans

By Mark Carter

Proposing A Toast To The King

by Gavin Martin

‘I feel like Bob Dylan slept in my mouth,’

Elvis Presley in a between song aside live in Las Vegas 24th August 1969.

‘Only one thing I did wrong, stayed in Mississippi a day too long,’

Bob Dylan ‘Mississippi’, ‘Love And Theft’, released September 11th, 2001.

Earlier this year I asked Sir Paul McCartney what he thought when he considered the perpetual live performance schedule Bob Dylan has maintained for over a decade. What would drive an extremely wealthy musician, a gentleman of a certain age, to keep up such a work rate? As ever McCartney had a ready, though perhaps too hasty, response.

‘Lack of a good woman, that’s the only reason for staying on the road at our age,’ he told me. There may be some truth in that; perhaps the failure of his marriages to Sara Lowndes and Carolyn Dennis and the lack of a stable single-partner relationship since have provided a spur for Dylan’s travels. But, seeing Dylan perform at the incandescent, endlessly inventive heights he’s scaled over the three decades I’ve been watching him, it’s hard not to conclude that, whatever the reasons behind why he’s doing it, Dylan has found a deep purpose in his nightly toil.

To see Dylan in full flow - from the raging torrents of electric fury, to the calm exultant moments when the musical interplay or three-part harmonies with Larry Campbell and Charlie Sexton recall backwoods settlers or clapboard gospel house meetings - is to see a fabulous carnival of Americana unfold, cross-cutting and enveloping time itself. He has subsumed and lived through so many epochs and influences - slave songs, blues truths, the white heat of 60s electric transformation, the fascination with Sinatra-style phrasing and 30s crooning. A 60-year-old man who has survived illness, hard living, the peculiar demands of being a cult icon in the culturally saturated Ground Zero 21st century, embodying all these elements and reinvigorating them, is both fascinating and inspirational. A Dylan performance is an encounter and a reckoning with many characters and personalities; in this respect a Bob show can summon up a similar feeling to watching old Elvis live footage.

The feeling can come at any point during the show. When he carouses gleefully into something as frivolous as ‘Country Pie’, slams into the rangy almighty bleakness of ‘Watchtower’, or beseeches and implores the muse or a higher power to come forth on the sacred bluegrass stormer ‘Wait For The Light To Shine’, Dylan is unabashedly celebrating a tradition, the tradition of individuality, wedded to a fond regard for and acute insight into the community from which such individuality springs. It is the same tradition that Elvis embraced with magisterial sweep. It was undoubtedly restrictions imposed by Colonel Tom Parker that prevented Elvis from ever leaving America to perform around the world, but Dylan traverses the globe with almost evangelical fervour. Eventually suffocated by a lifestyle which left him artistically impotent, Presley became a prisoner of his fame. He left the world as an icon, but his premature death deprived us of a fuller understanding of the world, and the humanity that nourished and influenced him.

Freed from outside control, the ‘Dear Landlord’ who would put a price on his soul, Dylan’s command of his music and artistic destiny and his ability to recreate and add to his legacy by being so ‘on form’ in his 6th decade ensures he expands on the legacy of the onetime rock 'n' roll king. Sure, an early Dylan death, or even an end-of-the-century expiration might have suited the requirements of those sad fuckers who think over 40s/50s/60s something per-formers shouldn’t make rock 'n' roll. Or, even worse, the empty-headed romantics who find glamour in early deaths. Those who think there’s a sacred link that ensures the good - Hank, Gram, Jimi, Buddy - die young, and that in a corrupting, energy-sapping business a shock early farewell is the only way to preserve dignity. What a sadly narrow-minded and reductive view of a culture which has always celebrated life, freedom and omnipresent beauty.

Like any child of the 50s drawn to the myriad possibilities thrown up by America’s musical melting pot, the young Robert Zimmerman was set free and transformed by the Memphis flash. It’s such a truism now that it’s easy to be blasé about the miraculous way music makes connections that would otherwise be impossible to imagine. Where else could the souls and fates of a dirt-poor son of the south and a middle-class product of the Midwest Jewish Diaspora become so entwined? Presley accelerated the culture by introducing the cool, glamour and daring which were a life-changing rebuke to McCarthy era racist America. The qualities that came through in Elvis TV appearances and in the records beamed into distant outposts by the magic of the airwaves became a potent catalyst in Dylan’s voracious intake of art, movies, literature and music.

The Elvis quote that begins this piece is delivered in an offhand, jocular fashion but it contains an almost Dadaesque truth; in the nine years that Elvis had been away from the American stage, Dylan had been the prime figure to utilise and explore the cultural space Elvis had created. Dylan’s genius took many forms, but his natural grasp of alchemy - adding surrealism, folk protest, the intensified barbed verse/prose of Ginsberg and Burroughs to the arena Presley declared open for business - must rank among his greatest attributes. As a performer and writer Dylan interconnected with a whole other school of learning, enabling him to adopt a chameleon approach to his public image that Elvis must have envied.

A captive of a dispiriting formula movie production line for most of the 60s, Presley remained socially and politically remote from Dylan and the era’s counterculture. The Vietnam War and The Beatles’ impact on America’s youth seemed to make Elvis a conservative God-fearing relic from a bygone era. But the counterculture hegemony had its own in built parsimony, shortsightedness and prejudices. As Elvis’s rampant afterlife has shown, his stature as a conservative relic was sorely over-hyped. Sure, he was a hopelessly confused drug-addled right-winger, but that shouldn’t be confused with artistic death. Indeed, the idea that Las Vegas became a kind of living tomb for him is loudly and triumphantly refuted by the astonishing performances on the 4CD Elvis Live In Las Vegas box set released in 2001.

In the earlier performances on the box set, recorded in 1970 and 1972, Elvis connects not just with his own past (and by extension the country, blues, gospel shouters and smooth-voiced crooners that influenced him) but also bonds deeply with recent pop. The funny, irreverent and illuminating between-song raps have the charm and candour of a storytelling showman raised on travelling fairs and tent shows. In his version of ‘Release Me’ he tackles the song as if it was a composition that deserved to hold The Beatles ‘Strawberry Fields’/’Penny Lane’ single off the top of the British charts, which certainly wasn't the case when Englebert Humperdinck’s sickly original did just that in the UK in March 1967. His versions of Ray Charles’s ‘I Got A Woman’ and Del Shannon’s ‘Runaway’ show an affiliation with his 50s peers that encompassed both love and competitiveness. And there can be no doubt that when Elvis disciple John Fogerty heard his hero sing ‘Proud Mary’ his heart must have nearly burst with pride.

Prior to his 1968 TV Comeback and his return to the live stage in Las Vegas Elvis had happened upon a Dylan song, ‘Tomorrow Is a Long Time’, on the Odetta Sings Dylan album. The song had not been released as a Dylan performance when Elvis recorded it in May 1966, but he completely understood its simple timeless poetry and elegant melodic flow. The performance was one of the most meaningful and beautiful by Elvis in a period when quickly knocked-out tat was the norm. You can hear the warmth and relief in Elvis’s voice as he sinks into a song that is spun from the same mastery of American folk culture, the seamless blend that exists only in music that inspired him.

Though neither the rumoured May session of 1971 or the 1972 duet on ‘If Not For You’ discussed in John Bauldie and Michael Gray's All Across The Telegraph compilation probably ever took place, the connection between Elvis and Dylan has always remained strong. In 1977 Dylan reacted badly when a man he never met but whose art had provided the basis for much of his life died. He later said that when he heard the news of Elvis’s death he ‘had a breakdown. If it weren’t for Elvis and Hank Williams I couldn’t do what I be doing what I do today.’ You can’t know what it’s like to be a frontier artist unless you actually are one yourself. Eric Clapton and Pete Townshend have spoken about the sense of devastation and emptiness they felt when Jimi Hendrix died. I wonder if Dylan felt something similar when Elvis went, if he heard the king singing that song ‘Its your baby, you rock it’. A cursory look at Dylan’s career after Elvis died suggests someone trying to do justice to the memory and legacy of his forbear.

Elvis's death coincided with the final chapter in the very public fracture of Dylan’s marriage to Sara Lowndes. Explicitly in the song ‘Sara’, allusively in many songs on Blood On The Tracks and Desire. With the sprawling much-derided movie Renaldo and Clara the relationship was laid bare with unnerving candour and, at least publicly, put to rest. It’s possible to view subsequent developments, the At Budokan album and the greatest hits tour, as Dylan’s equivalent to Elvis’s Las Vegas stint. Jerry Scheff from Elvis’s band joined on bass, while the girl backing singers recalled Elvis’s gospel muses The Sweet Inspirations. Presley had struggled to attain spiritual contentment while he was alive, a joy that can be heard most clearly in his gospel sides. Perhaps this fact was totally unconnected with Dylan’s conversion to Christianity, perhaps not. Perhaps it’s a measure of how completely absorbed Dylan has to be in a music and the culture that bred it (in this case sacred gospel music) to do it justice.

I first saw Dylan play live at Wembley Stadium in 1984, a sluggish muggy Saturday afternoon, the Real Live Mick Taylor band in a stadium setting. I found it so weird, unbelievable in a way, that up there was my teenage hero onstage. When I was a kid hearing Bob’s 60s music in the 70s he seemed, like Elvis, Little Richard, Buddy Holly and countless others must have to him when he was growing up, like a creature from another planet. I never thought I’d get to see him, and subsequently I’ve come to feel blessed that I’ve had the chance to see Bob frequently, but, as is often the way with stadium gigs, on my first encounter Dylan seemed remote, going through the motions.

Now I rationalise the memory - like any marathon runner in it for the long haul Dylan needed to pace himself, so perhaps he was already thinking of what lay ahead. If, as Mikal Gilmore recently suggested, Dylan lacked direction for most of the 80s, then for me the equivalent of the Elvis 68 Comeback TV special took place away from the cameras with the G.E. Smith band’s appearances in London and Dublin at the end of the 80s. The 80s had been a terrible stagnant period in rock history, the only living evolving embodiment of music from the source that I had apprehended was Van Morrison’s wondrous spiritual odysseys.

Van and Bob – buddies, touring partners, that’s another story altogether but when I saw Bob at Dublin and Wembley something cracked open, something Van hadn’t touched when I’d been seeing him. It came out of the cold metallic edge of the sound, the music’s frenzied rush with Dylan sneering and cackling into the whirlwind, unleashing one apocalyptic blast after another. It was the zeal and vibrancy I’d sought but only initially found in punk, filtered through mesmeric multi-levelled songs. Songs that were on this evidence inexhaustible, always ready to offer up new treasures and rewards if treated with vigilance and respect.

From that point on Dylan live shows became an all-bets-are-off, transforming experience.

Some have complained about the ragged quality of the early 90s shows, the supposedly drunken meander of Hammersmith 1991 and his much criticised 6 night run at the same venue in 1993. I was there that1s not what I heard or experienced. There was Dylan in loose limbed good natured mood, a curious and irascible old cove, somehow maintaining a mystique, an unknowability that seems to be an essential part of his armour outliving his own myth. Wherever he wandered off the beaten track he was still able at every single performance to pull something extraordinary out of the hat, cast a new and unexpected light on one of the jewels on his own ‘highway of diamonds’ or do something unique and loving to a song by one of his early friends and influences, Tomorrow Night sticks out.

I’ve heard certain critics give forth at the bar, surrounded by a coterie of friends and maybe even (God knows do critics have such things) admirers as they joylessly pick the show apart. These scholars of Dylan have a sneering know it all attitude and a way of reading the numerous blips and diversions that are intrinsic to Bobart. These would, if adhered to, suffocate his music. Dylan is all about making new discoveries even in songs that aren’t his own, songs as old and worn as Tomorrow Night where the very titles etch and explore the distance and relationship between the eternal road warrior/wandering minstrel and his audience.

Dylan, the kid who claimed to have hopped out of Hibbing all those years ago to join a carnival, has engaged in a life-long study of the mechanics of performing, and the beautiful symmetry of his art means that there are moments when the songs speak of nothing so much as his undying fidelity to the song itself. What has kept Dylan going out there, spending endless nights on the Lost Highway, if not the song? The song is the sacred ground where Dylan the performer and Dylan the fan - dig the frame of references, the unending glee that courses through his performance and it’s clear Bob’s as big a fan as anyone in the house at any Dylan show - comes face-to-face with his fans and influences. And of course, Dylan has not only been able to learn from the dangers of Elvis’s life lived as an icon but has also been able to master his own fate by having the song-writing talent, perhaps the greatest song-writing talent in American history, that Elvis never had.

What has kept Dylan going? The wind, the rain, gravity, many things, but partly a raging ego. It’s good fortune for the world at large that Dylan remains hungry, fascinated, bowled over by his own songs, the way they can comment on and shape the world, the way they defy time and space to find new meaning and pointed relevance in each successive era. The events of history may change but these songs he’s written are like mercury, always finding a new level, a way of fitting into current events and settings.

I have had some of the most remarkable and unexpected experiences of song-meaning transference at Dylan shows. To hear him play ‘Maggie's Farm’ in the Brighton Conference Centre, beside the hotel where ex-Premier Margaret Thatcher almost met her end in an IRA bomb blast, was a cauterising and incantatory moment. Why should this be so? I mean ‘Maggie’s Farm’ certainly wasn’t written about Thatcher, but the song is its own magical little world. Played with the zeal and urgency Dylan brought to it that night, it could mean whatever you want it to mean.

Of course with his own Russo-Judaic background and his keen awareness of the Scots, Irish and African songs and communities that feed the great river of American music, Dylan is an international performer in a way that Presley never was. He’s taking his art out into all manner of places that The King never knew existed, setting up his stall of magical potions anywhere and everywhere he can. I love that image of Dylan in the Howard Sounes book where he’s at a party and Maria Muldaur asks him to dance, and he says ‘I’d dance with you, Maria, but my hands are on fire.’ The young Dylan as a giddy can’t-keep-still manic ball of energy, the current of musical creativity running through him.

Look at a few of the places Dylan has played during the so-called Never Ending Tour. With an orchestra in Japan, on the banks of the river Mersey in Liverpool, at a sport hall in Belfast, a boxing arena in New York and a cultural centre in Prague. Take a look at the itineraries of his tours and you realise that getting out there and doing it every night, playing music and investigating the songs is for him a cleansing exercise good for mental, spiritual and physical health. But in these new contexts its also a means of exploration and discovery; who knows what possibilities or secrets the songs will offer up in the next town or at tonight’s show.

There’s no need for him to worry about what warped meanings, individual dramas or peculiar memories and meaning his audience take from the show. When it’s over he’s back on the road, ‘heading for another joint,’ a new audience waiting. The latter will no doubt be peopled by ever-younger faces. (This is the unwritten demographic increasingly obvious at Dylan shows. Last time he came here and toured in 2000 ‘his people’ regularly took younger less familiar faces from the back of the queue. A ploy rewarded with young faces suffused with joy at the end of the show, charging the venue with a mood of awe, optimism and renewal. And no wonder, name me another 60-plus-year-old performer who is so accessible in a live and in person situation, able to radiate cool and charisma without being an embarrassment, and I’ll show you Willie Nelson.)

Still, the setting and local history can do strange things to a song, or at least my interpretation of a song. Like when I saw Dylan perform over three nights at the Palace of Culture in Prague in 1995. It was said that a back problem had prevented strapping on a guitar, so every night he took the stage holding the mic with one hand, finger pointing towards the roof, singing ‘Down In The Flood’. Now that song, written during the Basement sessions, relates to a non-specific scene plucked from American settler history. But in Prague it seemed to be about something else entirely.

It was a strange few days. Between shows I’d wander the city, which had only recently been tagged as ‘the Seattle of Europe’ on account of the ever-increasing US student population who came to stay after the fall of Communism. I happened upon a photo exhibition by Dennis Hopper, shot during the early 60s. The juxtaposition of the ancient whitewashed cellar and the monochrome images of the 60s, James Brown beaming, surrounded by bikini-clad Californian girls, was striking. But not as striking or as haunting as the old Jewish town. During the war the Jewish population of Prague was almost completely wiped out. Terrazin concentration camp is located a short drive from the city, and the sense of loss and desolation hung heavy in the air on a walk through the old graveyard or the synagogue closed by the Nazis, attacked again in 1967. And a common sight there in the antique and book shops in the collections of religious relics was the Torah. The sacred Jewish symbol, a finger pointed heavenwards? Am I reading too much into it? Possibly, but that’s how songs work for me and Dylan is the master of the song.

Why has Dylan been able to go on long past the point where Elvis gave up the ghost? It’s the difference between being the director rather than the actor in the movie of your life; being a songwriter Dylan writes his own script. When he sings he can grapple with fate, destiny, politics and the price of love, sometimes all of them at once. He has dug deep into his and America’s past to define the present and ponder the future, an ongoing process highlighted by the World Gone Wrong and Good As I Been To You albums, the sleeve notes he wrote for the former illustrating the righteousness of his quest perfectly. Dylan is the song scientist attuned to the levels of prophesy, intrigue and resonances that exist there.

Is there an ending? So many of his friends and collaborators (Doug Sahm, George Harrison, Jerry Garcia) have gone in recent years, but Dylan keeps on mapping out euphorias and nightmares. He can’t help himself, he’s a cultural avatar, a living giant who will not be held to ransom by his past, who must keep driving forward.

When I consider the phenomenal depth, velocity and sheer fecundity of Dylan’s art it’s easy to see rock 'n' roll as a finite culture. I mean after Elvis, after Bob, who’re you gonna put up as a contender? Sure ‘enjoyable acts’, ‘useful performers’ have come along since Bob first rocked the world, but comparing many (any) of them to Dylan is like comparing the recently discovered new planet 2001 KX76 – actually little more than a boring lump of frozen rock – to the sun or the moon. Thankfully Bob’s steadfast promise to stay true to his art is repeated again and again in song. From the vow to keep on keeping on in ‘Tangled Up in Blue’ (a song held for so long at the same position, 5th song into the set, that it became a rallying point or staging post for whatever was to follow) to the warm wry resignation of ‘Mississippi’, birth state of Elvis, fount of so much American music.

And his songs, whether old like ‘It’s Alright Ma’ or new like ‘Tweedle Dee & Tweedle Dum’ cross time to stay true to the world and remain actively engaged with it. As the comic tragedy of the Clinton presidency was played out ‘Its Alright Ma’ sounded like a prescient up-to-the-minute commentary, riven with horror, haunted with paranoia, coursing with new life. And to see Dylan now in his pomp, his enthusiasm is infectious, I get renewed excitement for all types of music, music he doesn’t even touch – hip hop, techno, African, Latin, anything. Because the all-consuming energy and curiosity with which he approaches a performance rub off, you want to find out what more music can do to explain this world, or introduce you to new ones.

I’m the sort of dimwit who uses songs to understand the world. A song is a dead text, it only comes alive when it’s inhabited by a performer. Ray Charles singing the beautiful ‘I Can’t Stop Loving You’ is one of the most meaningful songs I know, an actualisation of long cherished truth which lies at the centre of everything from Joyce’s Ulysses to the Song of Solomon. It is easy to hear the song as a way of addressing the nature of the uncertainty, abandonment and heartbreak that Dylan felt when Elvis died. ‘I can't stop loving you/I've made up my mind/To live in memory of the lonesome times...’. Certainly, the way Colin Escott describes Elvis keeping on his toes in Las Vegas could easily have been written about present-day Dylan. ‘He recognised that he must mix it up. The show must be constantly reinvented, partly because there were returnees and partly because he needed to challenge himself and his band. He ran the gamut of American popular music; he had been listening intently to music since the mid 40s and knew 1000s of songs.’

When he got ill just after recording Time Out Of Mind Dylan told reporters when he left hospital that he had thought he was going to meet Elvis. He has said that during the recording of Time Out Of Mind he felt the presence of Buddy Holly, one of the first performers he ever saw, looming over the album, ‘guiding it in some way.’ Bob Dylan the giddy skinny guy who couldn’t dance with Maria Muldaur because his hands were on fire is still alive inside him. As he recently explained to Mikal Gilmore in a Rolling Stone interview, ‘I can’t really retire now because I haven’t done anything yet. I want to see where this will lead me because now I can control it all.’ What keeps Dylan going? A sense of duty and honour, a patriotism to the only America worth a damn – the America of Coltrane and Burroughs, Guthrie and Charley Patton, the need to keep the past alive, to keep the past in the present. Dylan’s mission, whether he sings sacred or secular, is profoundly spiritual. He knows that, as his friend and Sun Records founder Sam Phillips said when he heard Howlin’ Wolf, this is ‘where the soul of man never dies’.

And in his songs what sport there is to be had, what a feeling of immortality matched to the ever-present sense of mortality. The ever unwinding narratives full of cul de sacs, wrong turns and offhand revelations. Songs full of snares, jarring reflections, dark alleys that stretch into the night, brilliantly illuminated clearings where you do no more and no less than confront your own soul. And always coming back to something sweet, something simple, pledging his time to you and the song. So much Bob to listen to, so little time.

Recently, I’ve been listening to the bootleg of his Seattle 6th October 2001 show, the second show to feature songs from "Love And Theft". ‘It is time for Bob to park “Masters of War” away,’ says the sleeve note. ‘The notion it is the presence of weapons that cause war is obviously naive and misguided. Would Bob say the Boeing guys who designed the 757 or 767 are "Masters of War" since those planes were used in attacks?’ argues the writer. Sure 'Masters of War' was written long before the terrible events of September 11th but the song's central truths and the burning accusation contained in lines line ‘You that build the death planes/You that build all the bombs’ still hold true. Wars in our time rage before and after the Twin Towers collapse; the petrochemical and military-industrial complex are still the beneficiaries, humanity still the loser. Never mind the fact that, prior to the Twin Towers going down, Bush was widely seen as one of the weakest presidents in American history, elected and financed by less than scrupulous means. Bob’s inability to let the past rest is a rebuke to what Gore Vidal calls the United States of Amnesia.

There are treasures aplenty on the bootleg live album, but the song I’m playing now is ‘Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here With You’. I love what he does with his voice here; apart from reinventing himself as an electric guitar player in recent years Bob has also proved to be the most imaginative vocalist alive. His phrasing rivals Sinatra as he uses a whole bag of tricks – lacerating spite, nonchalant indifference, gruff declamations, searing firepower – to put his mood across. He delivers the lyric here in a gasping, breathless fashion, as if he were off to meet Elvis or Woody but came back, ailing but determined to reassert himself. As the band takes the melody at a slow waltz pace the line about the ‘poor boy on the street’ sounds more than ever like a ‘there but for the grace of God go I’ acknowledgement. But the whole tenor of the performance sounds like he’s restating the promise - making explicit the obvious connection to the audience.

The song fades out with guitar solo taking the place of the words. Bob plays a cyclical riff parlayed and buffeted by the band but the riff extends, ever renewing, coming back again and again. The waltz tempo hots up but the dance continues. He can dance now, Maria, he can really move. To paraphrase another great Jewish poet, Leonard Cohen, dance on maestro. Dance us to the end of love.

This article is dedicated to John Bauldie for the warm companionship and helpful introductions to so many lovely people in Prague, 1995.

Sounding Like A HillBilly: 'Moonshiner'

by Robert Forryan

|

I’ve been a moonshiner

For seventeen long years. I’ve spent all my money On whisky and beer. I go to some hollow And set up my still, An’ if whisky don’t kill me Then I don’t know what will. I go to some bar room, And drink with my friends, Where the women can’t follow And see what I spend. God bless them pretty women I wish they was mine, Their breath is as sweet as The dew on the vine. Let me eat when I’m hungry Let me drink when I’m dry, Dollars when I’m hard up Religion when I die. The whole world’s a bottle And life’s but a dram, When the bottle gets empty It sure ain’t worth a damn. |

The most exquisite version possible of the traditional song known as, among other things, “Moonshiner”: a version in which he so fully inhabits the persona of the Old Derelict narrator (the grace-kissed soul as well as the voice of the man) that it is eerie…’

Michael Gray, Song & Dance Man III

‘What’s extraordinary about this recording of “Moonshiner” is how Dylan summons up the strength of characterisation to cram decades of experience, disillusion and resignation into his voice, while his subtle guitar and understated harmonica work perfectly to support the edge-of-the-grave moonshiner’s vocals. It’s ironic that this recording was made when some traditionalists were complaining that the 22-year-old Dylan couldn’t even sing properly (remember the jibe of the coffeehouse owner recounted in “Talkin’ New York”: “come back some other day – you sound like a hillbilly. We want folk singers here”).’

John Bauldie, The Bootleg Series booklet.

The thoughts which follow come about as a result of e-mail correspondence between myself and Andrew Muir in which we had both expressed admiration for the performance of ‘Moonshiner’ which appears on The Bootleg Series set. It was then that I decided that I wanted to write about the song, though I had no idea what I wanted to say. It is easy to like a Dylan performance (easier than hating one), much harder to say anything of interest about it. For there are few things as dull as a eulogy. So much Dylan writing, and I do not exempt myself from this criticism, drifts into endless adjectives, similes and metaphors leading nowhere. The only point of writing for a magazine is to communicate – and to communicate you must have something to say which, in turn, means having thoughts to convey. So often it seems that adjectives, similes and metaphors become excuses not to think. They are so often meaningless. What I mean is that I come not to praise ‘Moonshiner’ but to talk about it and to see what happens.

This is always referred to as a traditional song, so we don’t know how or where this song originated, or if it was once the creation of one individual. I’m not convinced that it meets the Woody Guthrie criterion: ‘You can’t write a good song about a whore house unless you’ve been in one’. I’m not sure I agree with Guthrie’s unimaginative views and I doubt that the author of ‘Moonshiner’ ever distilled moonshine. Whether he or she ever did or did not, I can well understand why this song reached out to the coffeehouse generation on the cusp of the Sixties. Moonshining was foreign to their experience, as foreign as Woody’s dustbowl ballads and talking blues. But there was something about the old, mythic America that appealed to that generation; my generation. We had been brought up on Western films and TV cowboy series. We bought into the concept of rugged authenticity and its natural superiority to sophisticated urban culture (even though the latter was our inevitable destination).

We learned our liberal values and our sympathy for the outsider from so many Westerns where the lone stranger stood up for truth and justice against the baying mob. I am convinced that the Hippie movement owed some of its attraction to the fact that it echoed our assumptions about Native American Indian culture. For those movies had taught us to admire the 'noble savage' and to believe that his values were superior to those of our parents. In Westerns the bad guys were the bigots. You never heard the hero say: ‘The only good injun is a dead injun’. So, as we slid into late adolescence, the authenticity and ethnicity of folk music represented a natural home. And songs that spun tales of early, rural America or that evolved out of an oral culture were simply irresistible, if they were good songs. They still are.

All of which explains why ‘Moonshiner’ endured. It appears to have been performed and recorded by many artists and is known under other titles, among them ‘Moonshiner Blues’ and ‘The Bottle Song’. It often features on albums of folk material, being a particular favourite among those who compile collections of Irish drinking songs. The Clancy Brothers have recorded it as ‘Moonshiner Blues’ and their upbeat, party-style presentation - so different from Dylan’s - is a typical performance of this song. Dylan’s is the only slow version I have heard and it struck me as odd that Dylan could make something so beautiful out of this subject. What could possibly be attractive about a derelict, drunken moonshiner? As Debbie Sims wrote in Issue 4 of Homer, the slut: ‘For “moonshiner” read alcoholic because, although romantically put and sweetly sung, this is a song about a man whose whole life has been dominated by drinking and being drunk’.

As I typed those words, I realised I knew little about moonshining, so I did some investigating. I knew that moonshine was some kind of illegally distilled whisky, but that was about all. I know more now. Moonshine can be traced to Ulster immigrants who settled in the Appalachian mountains in the eighteenth century. They brought their own poteen-making methods with them, which evolved into moonshining. They were Protestants with a historical attachment to William of Orange. Hence they were known as King Billy’s men which, eventually, metamorphosed into Hillbillys – reflecting their political affiliations and their Appalachian homes.

In his book Almost Heaven: Travels Through The Backwoods of America, Martin Fletcher seeks out moonshiners in Rabun County, Georgia, ‘the last real stronghold of moonshining in America’. He meets a law officer whose father and grandfather were both moonshiners. ‘There weren’t no other jobs back then. Had it not been for moonshining we would have starved. That’s what bought shoes for our feet.’

Fletcher goes on: ‘There was something distinctly comic about moonshining in Rabun County, Georgia. Everyone knew which families made moonshine… where they got their supplies and which welding shops made their stills. The moonshiners were mean but they were characters… when caught in the act, moonshiners considered themselves honour-bound to try to scarper through the woods even though most were now old men and often inebriated by their own product’.

Moonshining goes on in the hills because they need to be near streams so that the stills can receive the cold running water they require. ‘The supplies and equipment are considerable. You need 800 pounds of sugar plus corn, yeast, malt and water to make 1,000 gallons of “mash”. You need several large wooden or plastic barrels in which to ferment the ‘mash’ and turn it into “beer”. You need the still itself – a copper or steel tank big enough to hold all the ‘beer’. You need bricks or breeze blocks to line a furnace beneath the still, 100-pound propane cylinders to boil the alcohol from the ‘beer’, car radiators in which to condense the steam and containers for the ensuing 100 gallons or so of moonshine’ – which is generally 95% proof.

Fletcher describes moonshiners as ‘an endangered species’. Moonshiners were making moonshine long before it was illegal. In 1794 farmers in Western Pennsylvania rioted at news of a proposed tax on whisky. ‘There was something almost romantic about these old rogues, and America would be a less colourful place without them’.

The first version of ‘Moonshiner’ I ever heard was by Bob Dylan on the Gaslight Tape from October 1962. In my early days of tape collecting names like the Gaslight and the Finjan Club and the Minneapolis Hotel simply dripped with nostalgia for the years of the Folk Revival. One imagines that this was not a one-off performance, but that it was a song Dylan had learned and that he carried with him as a usable item – a song to be pulled out when needed or when he was sufficiently interested.

The real subject of this essay is the outstanding ‘official’ recording of 12 August 1963 which appears on The Bootleg Series. As John Bauldie said, maybe there is a mystery attached to why it was recorded just then, since Dylan was clearly focussed on producing albums of original material. Nevertheless, he achieves an immaculate performance in what seems to have been a single ‘take’. This suggests he was very familiar with the song by this time. There is a story about the Japanese artist, Hokusai: it is said that he painted a lion every day in the hope of one day painting the perfect lion. I like to imagine that Dylan had been striving to perform the perfect ‘Moonshiner’ and, having done so on 12 August 1963, he felt no need to ever perform the song again. In my dreams.

There are, inevitably, differences between this later version and the Gaslight recording. Most obviously, on the earlier live recording there is no harmonica. Also, the first verse is reprised at the end, making four verses in all. And the second and third lines of the third verse become:

‘Moonshine when I’m dry,

Greenbacks when I’m hard up…’

In terms of the actual performance, the guitar work from the gaslight sounds less accomplished, the voice deeper. There is less stretching of vowels and emphasis is placed on different words, which is hardly surprising. It’s as if he’s still wearing the song in, like a new pair of shoes that are too tight-fitting. Everyone says of The Bootleg Series recording of ‘Moonshiner’ that Dylan sounds as old as the moonshiner himself. Andrew Muir once said he sounded as ‘aged as the oldest cask whisky’. I think this is true, and I love the performance, but if you listen carefully I think you will find that the voice truly ages towards the end of the first verse when it breaks on the words ‘don’t kill me’. Until then he’s still a young man.

The language of ‘Moonshiner’ intrigues me. I wonder exactly how old the song is and how much these lyrics are traditional and whether they have been adapted by Dylan at all? One somehow doubts that the lyricist ever was a moonshiner – there is something too poetic and too self-reflectively modern about the words for that to be believable. The sly character of the old man is cleverly drawn. Moonshining being illegal he necessarily practises the art of deceit. This aspect of his nature is doubly alluded to in that the still is hidden in a hollow, and by the fact that he chooses to drink where:

‘The women can’t follow

And see what I spend…’

Women? Surely he means wife? Don’t men habitually try to hide their pleasure-spending from their women, be it on alcohol, books, CDs or football? Or does this line allude to a further deceit of an adulterous or bigamous nature? The following lines:

‘God bless the pretty women

I wish they were mine…’

seem to indicate that faithfulness is not on his agenda. In fact, it seems that there is no area of life in which this moonshiner is to be trusted.

The lines that I always lovingly return to when I’m away from the CD player and playing the song in my mind are these:

‘Their breath is as sweet

As the dew on the vine…’

I think that a woman’s breath is not the feminine quality that would most appeal to the average male nose (how many people really have sweet breath anyway?). Debbie Sims contrasts the breath of the women with that of the moonshiner and suggests that the contrast is a part of their attraction to him. But surely, it is the scent of a woman that is more alluring than her breath? And what is truly attractive about dew is not its smell (does it have a smell?) but its visual beauty as, say, it is caught and tinted by the sun, or its gentle dampness – and dew, that foggy, foggy dew, has long held a sexual connotation in folk music. But in this performance breath is sweet, for, as John Bauldie pointed out, these are what Dylan himself called ‘exercises in tonal breath control’. Listen to the way he extends the ‘a’ in that first line, or ‘all my’ in the third line. The way Dylan uses his breath here is as sweet as… it’s just sublime. Even more sublime than the lovely ‘Copper Kettle’ in which he revisited the moonshining theme in 1970.

In the end, it’s the performance that matters. He doesn’t sound like a hillbilly, this is a folk singer we hear.

Bow Down To Her On Sunday

by John Gibbens

Among the reviews of The Nightingale’s Code, my ‘poetic study’ published by Touched Press in October last year, one common note was sounded. Whether the reviewer was appreciative (Paula Radice in Freewheelin’), dubious (Jim Gillan in Isis) or dismissive (Nigel Williamson in Uncut), the same point got picked on by each of them to demonstrate my occasionally – some said, and some said chronically – wayward thinking. This egregious fallacy was my suggestion that ‘To Ramona’, in its title, refers to the Tarot, and in particular to two cards, the High Priestess and the Wheel of Fortune. I’ll restate my case in a moment. Here is how Paula Radice responded to it:

‘I can accept… Gibbens’s view that the cycle of the first seven albums (up to the “cycle” accident!) turns around a midpoint of “To Ramona” on Another Side Of Bob Dylan… Where Gibbens loses me is then putting forward, as part of the justification for this thesis, that the first part of the title – To Ra – means Tora, the Tarot, and the Latin rota or “wheel”, and that these were deliberate inferences on Dylan’s part. It just seems unnecessary, indeed counter-productive…’

And this was Nigel Williamson’s view:

‘… if you didn’t see the significance in the fact that the first four letters of the title “To Ramona” spell TORA, which is the word on the scroll held by the High Priestess in the Tarot pack, then your appreciation of Dylan is superficial indeed. You’re probably the sort of person who doesn’t even appreciate that his early lyrics are characterised by the use of the metrical foot known as the anaepest. [sic]’

This is mere misrepresentation. I do not imply – certainly not in the section under discussion here, and I hope nowhere else – that someone’s listening which is not informed by the circumstances or connections I fetch to a song, whether from far or near, is therefore shallow or wrong or inadequate. If I propose a thought you had not already had, or convey some fact you didn’t know, am I thereby calling you ignorant? No: though not being able to copy the correct spelling of a word – like ‘anapæst’, say – from a book you are reviewing could be considered ignorant.

Never mind. For now, I’m interested in why this ‘To Ra’ idea of mine caught the flak. But first let me explain it a bit more. My argument seems not to have been clear in the book, since none of the three reviews I’ve mentioned restated quite what I thought I had proposed. I’m not suggesting that Dylan juggled the four letters TORA to get Tarot and also ‘rota’, the Latin wheel, or that he would ever expect anyone to follow such a leap if he had made it.

The letters appear like this, ‘TORA’, on the High Priestess card, and they also appear at the four cardinal points around the Wheel of Fortune, as T–A–R–O, just as N, E, S, W appear on a compass. But Dylan did not need to connect these himself – the link is made by A.E. Waite, who designed the pack in question, in his accompanying book The Key to the Tarot. He points out the letters and explains that they can be read clockwise from T in the ‘North’ position, back to T again, to spell ‘Tarot’; or from R in the South, clockwise, to read ‘Rota’; or from the T, anticlockwise, as far round as A, to read Tora. He further points out that this is the word on the High Priestess’s scroll, and that it stands for Torah, which is the Hebrew for law, or instruction, or direction, and the name given to the first five books of the Bible.

Before we go any further, there are a few supporting points I should make. First, these writings of A.E. Waite are not at all obscure or esoteric. The Waite pack is probably the most popular form of the Tarot to this day, and would have been by far the most likely pack you’d come across in 1964, back before the general revival of the ‘occult’ led to a profusion of new designs. Likewise, Waite’s book is one of the favourite beginner’s guides to the cards and has been reprinted many times. I bought it as a cheap, recently published paperback in the 1980s.

Second, we know that, many years later, Dylan took an interest in the Tarot and the Waite pack in particular. He ‘quotes’ the Empress card from it on the back sleeve of Desire. Even from a cursory look at the symbols and the ways of interpreting them, the influence of cartomancy – and especially the kind of symbolism that Waite draws from, mixing the biblical with the magical – can be seen both in Street-Legal and Renaldo & Clara. In the film, when Joan Baez appears as the Woman in White clutching a red rose, she echoes both the Empress, who wears a white gown sprigged with red roses, and the High Priestess herself, who wears a blue mantle over what I take to be a shimmering white gown. (It’s coloured white in places and blue in others – I think to give a moonlit effect. She has the full moon set in her crown and the crescent moon at her feet, and sits as it were in an alcove between two pillars, one black and one white.)

In Waite’s little instruction pamphlet that comes in the box with the cards, the High Priestess is said to represent, in a reading, ‘the woman who interests the Querent, if male; the Querent herself, if female’. She also stands for ‘silence, tenacity, mystery, wisdom’. (Which is about as much detail as any of the biographers have been able to disclose about the character of Sara Dylan, isn’t it?) For all her virginal and remote attributes, it’s the Priestess and not, for example, the much more ‘earthy’ seeming Empress, who signifies a sexual and romantic relationship with a woman.

Now perhaps we can see a link between the High Priestess and ‘To Ramona’, with its peculiar blend of ‘high’ philosophising and sensual romancing. It doesn’t seem to me far-fetched to suggest that the song arises from the combination of experience of and meditation on this image. It’s interesting that ‘Torah’ should mean instruction or direction, given that the song mixes several direct instructions – ‘come closer, shut softly your watery eyes’ – with its more abstract teachings – ‘Everything passes, everything changes’ and so on.

Here I should make a third substantiating point. This stuff about the Tarot may or may not interest you, but I think you’ll agree that it is directly relevant to one period of Dylan’s work at least; that he clearly had its symbolism in mind about the time of Street-Legal and Renaldo & Clara, and that he invites us, as openly as he has ever done with any outside source, apart from the Bible, to use the Tarot as a ‘key’ to some of his images. But that was then. Is it likely that he’d known about, let alone thought about the cards, and used their symbolism as a source for his art as early as the mid-1960s?

Well, the biographical evidence suggests that he learned about the Tarot from Sara, whom he most likely met sometime in 1964. Now here’s a nice piece of circumstantial evidence. The cover photograph of Bringing It All Back Home was taken in the first weeks of 1965. Put the Empress on the back cover of Desire alongside Sally Grossman, the lady in red on the front of BIABH (much easier to see if you’ve got the LPs). Do my eyes deceive me, or is that almost the same pose? I hope I’ve made a case, at least, that Dylan’s quite deep knowledge of the Tarot could go back a long way before Renaldo & Clara.

While I’m making this defence, I’d like to make a retraction too. In my book I claimed of the Dylans, ‘We can date their meeting fairly accurately’. This was showing off, because I was pleased with myself for having tracked down two decaying hurricanes that hit New York in the autumn of 1964 – on 14th and 24th September – and concluded that this must pinpoint the ‘tropical storm’ that is mentioned in the song ‘Sara’ as marking their meeting. They were the only truly tropical storms to reach the northeastern seaboard that season, but it’s still just a guess, and a far cry from ‘fairly accurate’ dating.

I’d much rather, really, that they’d met a lot earlier, before 9th June 1964, for example, when Another Side was recorded. Then maybe that storm could be the tremendous one of ‘Chimes of Freedom’, and they could be that ‘we’: ‘Starry-eyed and laughing as I recall when we were caught, / Trapped by no track of hours…’

The ‘message’ of ‘Chimes of Freedom’, with its Sermon on the Mount echoes, also chimes with that line in ‘Sara’ – ‘A messenger sent me in a tropical storm.’ (The sentence is ambiguous: he was sent along by the messenger is the top meaning; but it can be read grammatically as ‘How did I meet you?… [By means of] a messenger sent [to] me in a tropical storm.’)

If a ‘real-life’ Ramona is required, Sara is a much more natural one than, say, Joan Baez. The Tarot doesn’t seem like Joanie’s bag, and nor do the confusion and tears that Ramona shows. But the feeling of being torn that the song describes wouldn’t be surprising in a woman, like Sara at that time, with a young child and a marriage falling apart.

Identifying Sara, or anyone else, with Ramona doesn’t tell us much about the song (though the song might tell us something biographically about a relationship). But associating Ramona with the High Priestess, it seems to me, does add something to the song. It strengthens our sense of Ramona’s dignity – ‘the strength of your skin’, those ‘magnetic movements’ – that counterbalances this temporary bewilderment and weakness. It heightens the feeling of reciprocity. If Ramona is, in her better self, like the Priestess, then she is herself the source of wisdom and knowledge, and this situation where the singer is spelling out the facts of life for her could as easily be reversed, as the last lines acknowledge: ‘And someday, baby, / Who knows, maybe / I’ll come and be crying to you.’

As the precursor to a string of notable ‘advice-to-a-woman’ songs – ‘It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue’, ‘Like a Rolling Stone’, ‘Queen Jane Approximately’ – the Priestess image reinforces a basic respect that underlies them, that keeps them, somehow, despite their outspokenness, from sounding merely gloating or contemptuous.

Much has been said of the viciousness, the sneer, the anger of ‘Like a Rolling Stone’, but what has kept it alive so long is the way that this is mixed with a kind of stateliness. And this stateliness pertains to the person that the song describes, just as it does in ‘Queen Jane’. We may see the women, in the images, stripped of their trappings of comfort, prestige and power, but in the music we see them somehow the stronger for it. What makes the songs moving and lasting is the feeling that Dylan conveys, in everything apart from the words, that he’s not crowing ‘I told you so’, but saying rather, as he says Ramona says, ‘You’re better than no-one / And no-one is better than you’.

That is a philosophical constant of Dylan’s work, a ‘something understood’ that keeps him on a level with us, however ostensibly preaching or haranguing or even vituperative his words. And this is what enables them effectively to preach and teach.

My reason for mentioning the ‘To Ra’ hypothesis in The Nightingale’s Code was not so much to do with the High Priestess as with the Wheel, the Rota. Of course, this period of Dylan’s life was a ‘turning point’. What intrigued me was how consciously he seems to have realised it. The image of a wheel or ring is deliberately evoked in the front of Bringing It All Back Home, and it occurs in that key song ‘Mr Tambourine Man’, in the tambourine itself and in the ‘smoke-rings’ of the mind, and also in ‘To Ramona’: ‘my words would turn into a meaningless ring… Everything passes, everything changes’.

I go on to discuss how Another Side itself seems to rotate around this central point, ‘To Ramona’, turning from a positive first side – Incident, Freedom, Free, Really – to a negative second – Don’t, Ain’t, Plain, Nitemare and so on; turning right round, in the end, from ‘All I really want to do is, baby, be friends with you’ to ‘It ain’t me you’re lookin’ for, babe.’ From there I go on to suggest an even wider wheel, still centred on ‘To Ramona’, with the three folk albums on one side and the three rock albums on the other. And there I leave you to decide for yourselves with what kind of consciousness Dylan could have created the ‘centre’ of such a wheel, when he could not know where it would stop.

Which brings me back to my original question, why the reference to such esoterica as the Tarot got picked up. If there is any substance to my idea of a larger organised form to the whole sequence of Dylan’s first seven records, then how did it get organised? It suggests a shaping power of imagination far beyond what the ordinary Selfhood could encompass.

The Canadian critic Northrop Frye wrote in Fearful Symmetry, his inspiring study of William Blake, ‘If a man of genius spends all his life perfecting works of art, it is hardly far-fetched to see his life’s work as itself a larger work of art with everything he produced integral to it’. This idea he expanded further in Anatomy of Criticism, which might flippantly be called the prequel to Fearful Symmetry, since it outlines the vision of all literature which he had seen through his reading of Blake: ‘It is clear that criticism cannot be a systematic study unless there is a quality in literature which enables it to be so. We have to adopt the hypothesis, then, that just as there is an order of nature behind the natural sciences, so literature is not a piled aggregate of “works”, but an order of words.’

My aim in The Nightingale’s Code was simply to set such a vision of Dylan’s work afoot. To be honest – not wanting to launch an anti-advertising campaign – this was what I’d missed in the critical studies I’ve read. The observations accumulate but they don’t seem to assemble into a picture. It’s not clear what the details are details of.

I wanted to show how, for example, song might relate to song on an LP; how LPs themselves might be constellated in phases or cycles – or chapters, if you like. Also, what might be constants of the whole work, the forms and images that speak to each other across it. In this I seem so far to have failed, since the critic who was most responsive to the book, Paula Radice, took exception to precisely this schematic aspect of it.

The tenor of most Dylan criticism at the moment is to celebrate the diversity of his work – to multiply its breadth and open-endedness. At the same time, I believe the perception that Dylan’s work is a whole, even while it can’t yet be seen whole, is well established – for example among the readership of this magazine. Many people – I would guess it’s probably most of the people who enjoy his music – have the sense that it’s worth getting to know extensively. There may be a certain consensus on the highs and lows, as well as our own personal charts, but I think most of us feel that the body of work adds up to something more than a selection of its highlights, however collectively edited. Don’t you also find yourself more often drawn back to, and getting more out of, a Dylan record you regard as second-rate, than is the case with many a first-rate record by other artists?

Of course there are two important obstacles to studying Dylan as Frye studied Blake. One is that he is alive, and we can’t claim to see the work whole while it is still unfinished. The other is that it’s not literature. What constitutes the canon of Dylan’s work? ‘Mr Tambourine Man’, say, is an element of it, but what is ‘Mr Tambourine Man’? The first track on Side 2 of Bringing It All Back Home, or any one of the hundreds of other performances by Dylan himself, or for that matter by anyone else?

In my book I opt for the official releases as forming a canon within the canon, so to speak. The artist himself gives some warrant for this. He doesn’t, at least in later years, give his songs in concert until they’re out on record – so that the live versions must to some extent be heard as subsequent variants of an original. The profusion of variants with Dylan has no real parallel among the poets of literature, but it’s not an alien thing altogether.

The canons of poets are mostly synthetic; few are crystalline, fixed and simple. ‘A’ poem is often surrounded by a penumbra of other versions, earlier forms and later revisions. The ‘death-bed collected’ is the usual basis of a canon: the poems, and the forms of them, that were last authorised by the poet in their lifetime. But this needn’t prevail. Whitman, Wordsworth and Auden, for example, are all felt to have done injustice to their early work with later changes, and so there is often an alternative version of the poems as they first appeared.

The canon of William Blake is, in fact, a striking anomaly something like Dylan’s. Not because Blake showed uncertainty in constituting his works: of him, more than any other English poet, we can say that the canon is ‘writ in stone’, since he personally, laboriously engraved in copper every single letter and punctuation mark of his completed poems. But the works he conceived are unities of word and image, and each copy of one of his Prophetic Books is unique, a combination of printing and painting.

If he had had the audience and the resources, there might be as many Miltons and Jerusalems as there are ‘Mr Tambourine Men’. Well, almost. So the words of one of the poems reprinted in a book are not the actual thing that Blake made. This is why his work, though its influence grows year by year, is still regarded as obscure: because it is, and will be until there is a permanent free public exhibition of all his illuminated books together. At least there is, at last, two centuries on, an affordable one-volume, full-size reproduction (The Complete Illuminated Books, Thames & Hudson, 2000, £29.95).

For future generations, the canon of Dylan’s work will pretty certainly include the concert recordings, studio outtakes and so on which are currently collected and curated by the fans. This is a fittingly democratic way for it to form, outside the ambit of the academies which Dylan has often berated. But I predict that the official albums will be the central structure around which the rest is organised, and I think that Dylan appreciates this, despite his pronouncements in periods of discouragement that he didn’t really care about making records, so long as he could perform. This was when he didn’t particularly care about making new songs either: compare and contrast with the clear sense of achievement that comes through in interviews now at having made ‘a great album’ in "Love And Theft".

In an album, a set of songs is organised into a greater whole; in a concert they are organised into another, different whole. ‘Sugar Baby’ belongs at the end of ‘Love And Theft’; in a concert we might discover that it also belongs perfectly between ‘Buckets of Rain’, say, and ‘It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue’. This independence of the songs, their constant movement in relation to each other, does not diminish the order of the canon, but serves to knot it all the more integrally together. It may seem to have no parallel with the way that poems appear in a poet’s book, always the same words on the same page. Yet what Dylan does for us with his songs is quite close to the way that poets begin to be read when we know them well enough, so we can turn from one poem to another, cross refer, even read two poems side by side, nearly simultaneously.

When I called my book The Nightingale’s Code I was obviously playing on the idea that Dylan is an enigma – that Dylanologists are still engaged in trying to ‘decode’ his lyrics. But I meant it more seriously in the sense of a ‘code of behaviour’, like the ‘code of the road’. The word comes from the Latin codex, which means originally a block of wood. A block was split to form leaves on which to engrave important and permanent documents, such as laws. In English the word ‘code’ – before it became synonymous with ‘cipher’ – meant ‘a digest of the laws of a country, or of those relating to any subject’ and ‘a collection of writings forming a book’ (Oxford English Dictionary). In other words, it’s an alternative term for the ‘canon’ that I’ve been using here. To my mind, the ‘code’ in Dylan – in the secret-language sense – is simply his ‘code’ in this second sense: the integrated body of work in terms of which each part can be interpreted.

The resistance to my ‘To Ra’ idea – an arcane reference couched in a form rather like a cryptic crossword clue – springs I think from a generally healthy scepticism about hidden meanings and skeleton keys. Ingenious and cryptological explanations have fallen out of favour, due to their own excesses, and Dylanology pursues more sober, empirical and encyclopaedic projects. What was valuable, however, even in such wild theories as A.J. Weberman’s, was their search for the ‘thread’ of Dylan’s work. Weberman’s ‘plot’, applied to Dylan’s career up to the early Seventies, was the story of a Revolution betrayed by its leader (as far as I can make it out). He supplied for Dylan’s country music the cry of ‘Judas!’ that had earlier been flung at his rock music.

If we don’t find schemes like this – or Stephen Pickering’s interpretation of the poet’s progress in terms of the Cabala and Jewish mysticism – satisfying, it’s because they seem reductive. Tying the form of artistic creation to another, extrinsic form, they restrict rather than expand its scope.

The problem with approaching poetry or song as ‘code’ is that code in itself is meaningless. Once it has been deciphered it is ignored; it adds nothing more to the real message it was concealing. If a song is coded in this sense, then all our responses to what it ‘seems’ to be about would be like delusions. Hence our natural hostility to what is effectively a destructive form of interpretation. But a song can have ‘hidden’ or ‘other’ meanings in another way: not as concealed within it or ‘behind’ it, but hidden in the sense that we don’t see them until we see the larger form of which the thing we are looking at is a part. These are the relations that give a work of art its third dimension, its depth.

The larger form is the artist’s body of work and also the ‘order of words’ that Northrop Frye speaks of, the total form of literature. With Dylan, of course, we cannot say simply ‘literature’. One of the reasons he strikes us as such an important figure is that an integral view of his work has to place it simultaneously in both literature and ‘popular music’ (there’s no word as neat as ‘literature’ to describe this other field); and therefore he unites, or reunites, these estranged relations. He’s not alone in doing this. Burns, Brecht and Lorca are three who spring to mind as co-conspirators, but their work has all ended up as books, and been subsumed into literature, and Dylan’s will not be subsumed.

In fact, at the moment the emphasis is the other way, partly because of the nature of Dylan’s writing in its current phase, and partly because that ‘other’ field – the golden triangle that lies between points A (for art music like avant-garde jazz), C (for commercial or chart music) and F (for the various shades of ‘folk’ music and field recordings) – is at present, thanks to CDs and expiring copyrights, being formed into a canon of its own. In this respect "Love And Theft" is not ‘retro’ at all, because its encyclopaedia of ‘thefts’ goes hand in hand with a whole new level of documentation of its sources.

Reference-spotting can be illuminating, but it’s not the end of hearing Dylan’s music in an integrated way – and it may not even be the beginning. Let’s say that the 12 songs of "Love And Theft" allude to 100 other records (it’s probably not an overestimate): we don’t necessarily get farther into it even if we track down every last one of them. The important thing would be to listen back and forth, so to speak. To know the why of one reference will tell us more than to know that 99 others exist.

Which brings me back to my Tarot reference. The point is not that ‘To Ramona’ is really about a playing card instead of a person, or that Bob Dylan once practised divination. The point is that the High Priestess helps us see the ground on which Ramona moves, a harmony to her melody, if you like. A further quote from Northrop Frye, from Fearful Symmetry, may suggest how John Donne and Woody Guthrie, Tarot and ‘corpse evangelists’, ‘To Ramona’ and ‘Chimes of Freedom’ all come to combine in the form we know as Another Side.

Speaking of the Renaissance humanists, he points out: ‘They had in common a dislike of the scholastic philosophy in which religion had got itself entangled, and most of them upheld, for religion as well as for literature, imaginative interpretation against argument, the visions of Plato against the logic of Aristotle, the Word of God against the reason of man.’ He goes on to say: ‘The doctrine of the Word of God explains the interest of so many of the humanists, not only in Biblical scholarship and translation, but in occult sciences. Cabbalism, for instance, was a source of new imaginative interpretations of the Bible. Other branches of occultism, including alchemy, also provided complex and synthetic conceptions which could be employed to understand the central form of Christianity as a vision rather than a doctrine or ritual…’

It remains only to say that in Dylan’s case the matter of references and possible allusions is slightly complicated by that aspect of him that plays the Riddler or the Jokerman. ‘Rainy Day Women #12 & 35’, anyone? Well, 1, 2, 3, 5 are the first four prime numbers, and the next in the sequence is 7, and this is the first track on Dylan’s seventh album. I’ve also speculated that they’re the numbers of hexagrams in the I Ching – something else he’s known to have been interested in, and once refers to openly: ‘I threw the I Ching yesterday, said there might be some thunder at the well.’

An interesting reading in the light of Blood on the Tracks, though ambiguously put. I’d assume it was hexagram 51, Thunder, moving to hexagram 48, The Well, but it could be the other way round. Either way, the judgment on The Well is fitting for that fresh tapping of former powers: ‘The town may be changed, but the well cannot be changed. It neither decreases nor increases…’ And the Thunder of the I Ching, as described in the translator Richard Wilhelm’s commentary – ‘A yang line develops below two yin lines and presses upward forcibly… It is symbolised by thunder, which bursts forth from the earth’ – is something that might well be called Planet Waves.

So to return to Nos 12 and 35 – hexagram 12 is Standstill or Stagnation, and Blonde On Blonde is all about stasis and stuckness. Richard Wilhelm comments: ‘This hexagram is linked with the seventh month… when the year has passed its zenith and autumnal decay is setting in.’ That seventh album again, and according to my seasonal arrangement of Dylan’s records, Blonde On Blonde is an autumnal work.

And 35? That’s called Progress and the image is of the sun rising over the earth. What lies beyond the stasis of Blonde On Blonde is, whaddyaknow, a New Morning.

These are plausible references for the numbers, if you think they are there for any reason. They’re also both biblically important. Twelve, as in tribes and apostles, and 35 as a number of the apocalyptic proportion, as stated in the formula of Revelation, ‘a time, and times, and half a time’, i.e. 1 of any unit, plus 2 of it, plus a half = 3.5 and any of its multiples, like 7, or 70, or 35.

The formula occurs, in fact, in chapter 12 of Revelation: ‘And to the woman were given two wings of a great eagle, that she might fly into the wilderness, into her place, where she is nourished for a time, and times, and half a time, from the face of the serpent. And the serpent cast out of his mouth water as a flood after the woman, that he might cause her to be carried away of the flood.’ (‘Rainy Day Women’, anyone?) ‘And the earth helped the woman, and the earth opened her mouth, and swallowed up the flood which the dragon cast out of his mouth. And the dragon was wroth with the woman, and went to make war with the remnant of her seed, which keep the commandments of God, and have the testimony of Jesus Christ.’ (‘They’ll stone ya when you’re tryin’ to be so good’ anyone?)

Yet the suspicion is strong that they could actually be any numbers, and that what they mean at the beginning of the record, attached so arbitrarily to a title so arbitrarily attached to its song, is: prepare to be baffled.

And yet, and still – why those particular numbers? Follow the Riddler into the labyrinth, but let a thread unwind as you go, or you may end up lost in there.

A final quote from Northrop Frye. Of Blake he says: ‘He is not writing for a tired pedant who feels merely badgered by difficulty: he is writing for enthusiasts of poetry who, like the readers of mystery stories, enjoy sitting up nights trying to find out what the mystery is.

Content from Other Issues

Ain’t Bob About A (Singin’) Cowboy?

By Pat Fitzgerald

(In which the argument will be presented that Bob Dylan possesses a “cowboy attitude” and may have garnered some song lyrics from dialogue rendered from the western movies.)

He enters his shows to the tune of Rodeo Hoedown

Duded up like a cowboy goin’ to town.

He don’t give no bullshit—no meaningless patter

As he stands “at the keyboard with a gunslinger’s swagger.”1

He’s swung a lasso in the movies2 atop a horse

And caught him a turkey—off camera, of course.

He wrote that movie’s soundtrack and when asked why,

“I had a fondness for Billy,”3 was his reply.

He did the Kid right, composed the perfect atmosphere.

Just head out to Lincoln4 where it’s played everywhere,

In all the town’s museums for all to enjoy.

Quite the achievement for a Midwestern boy.

Did those western movies get into his brain

When he was a kid on the Iron Mountain Range?

Did he catch bits of dialogue that stuck with him,

Heard over the Lybba’s5 kids’ matinee din?

There was this line in The Law vs. Billy the Kid.6

Did Bob want to use it, the same as Billy did?

“We still got better’n twenty miles to go before we get to town.”

Ain’t that like he told us in “Cold Irons Bound”?

“I don’t think about it,” was heard in The Great Divide.7

Could poss’bly, in his subconscious, those words did reside

Till he thought about the daughters who put him down?

Had he pictured them dressed in Miss Kitty-style gowns?

In a Hopalong8 flick a dance hall girl once said

Something that, maybe, lingered long in Bob’s head.

“She doesn’t know whether to kiss him or kill him.”

Was it a whim a lyric like that’s in “Standin’”?9

I know, it’s been said I watch too many westerns,

An tyin’ those quotes to Bob is simply conjecture.

But look at his music—it’s quite plain to see

He know the source-ballads of western melody.

In Bonnie’s apartment10 he sang “Wild Mountain Thyme.”

In New York, at the Gaslight,11 “Barbara Allen” he chimed.

Songs from the Isles—“”Wagoner’s Lad”, “Eileen Aaron”

All traveled the wide ocean for our boy to croon.

Those ballads wound their way to the Appalachians

And soon bore the imprint of a brand new nation.

From the mountains of the east, they traveled out west.

Where new tales spun off them, as Bob’s own song suggests.

To the sound of a traditional Irish tune

Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Willie dies is a saloon.

But first he roams from the White House to the Rockies

Displaying the traits a legend should embody.

Western ditties penned by Bob, they ain’t very many.

Yet when rip-roarers all, there ain’t need for plenty.

He learned his lessons well ‘bout how a tale to tell

An’ once he gets a-goin’, his cowboy spirit swells.

“Romance in Durango”—chili peppers, thund’ring guns,

An outlaw with his querida on the run.

’Tis a Mexican yarn that’s filled with tragedy.

South of the border cowboys can’t flee adversity.

The haunting “Angelina” bears a western tinge

With allusions to card games that no one can win.

There’s bandits and shotguns, the sky changing shades

And the hero must flee after his sad serenade.

There’s folks in a song I feel is Bob’s western best,

Equal to that flick in “Brownsville Girl”, starring Greg Peck.

Lily was a gal about whom films could be written.

The mysterious Jack of Hearts—for him she was smitten.

Jealousy was Big Jim’s fatal flaw. Rosemary

Faced the gallows, the deadly price her good deed carried.

The setting, side plots, action, psychology

Is everything that’s needed for a well-told movie.

Wait—movies!? Let’s return once more to different times

To that boy in Hibbing whose imagination shines

When a bit of movie conversation sparks

Something in his head that leaves an indelible mark.

“He had it comin’,” said Gabby Hayes.12 His voice intones

The timbre of the killer of Hezikiah Jones.

And in Street Legal, after Bob got sober,

Did he flash on Hoppy’s “ . . .We gotta talk this over.”?13

In Texas,14 ‘bout two drifters close as brothers,

“We’ll meet again someday,” says one pal to another

In a scene not unlike “Tangled”15 on the roadside,

When he leaves the red-haired lady to roam far and wide.

In The Gunfighter16—“Bring that bottle over here.”

Is said by Greg Peck. Yeah, yeah, that’s not obscure.

Could be chance that it’s in, “Be Your Baby Tonight.”17

I ain’t sayin’ my guess is necessarily right.

But look at Gene Autry’s villain—quite often Big Jim.18

Remember The Last Waltz, that hat with the big brim?

That same wide fedora is worn by Autry’s bad guys,

As is a pencil-thin mustache, like on Bob’s lip did rise.

There’s two simple words from Twilight on the Rio Grande,19

That I’m bettin’ in Bob’s memory did land.

“Senor, senor,” from “Tales of Yankee Power,”

A song more of Armageddon than of western lore.

And in one Autry movie, a bus roles down the road.20

Is this where Bob’s restless feeling was first bestowed?

Gene kept a-traveling to get to his next gig.

Bob hits the highway in the same type of rig.

Is it possible movies shaped Bob’s attitude

And that’s how he became a western-type dude?

Or perhaps you don’t see what I’m trying to say.

And if you don’t agree, that’s perfectly okay.

That he’s worn to Elton’s party21 and a boxing match.22

His western boots are legendary, at least to me.

With black and white flames, they’re quite delightful to see.

But that don’t count for much, because it’s just attire.

To gain the cowboy attitude, one must reach higher.

It’s not just about cattle, a lifestyle’s involved,

And a respect for freedom’s a definite resolve.

Who among us can deny that Bob is freewheelin’?

The life’s choices he’s made would leave others reelin’.

He stays on the road ‘cause settlin’ down ain’t his way.

When you get right down to it, he just wants to play.

I reckon he won’t quit. He’ll keep on singin’ his songs.

Let’s hope that his wanderings remain wide and long,

And he’ll always move forward with no regret

Till, like an ol’ cowboy, he’ll ride into the sunset.